I

started the April Poem a Day challenge and shared some of my work here,

but as you noticed I quit after a few poems. This tends to happen to me

a lot when I try this kind of challenge. I toodle along pretty well at

first, then I find other things demanding my attention and I move on to

those things. It happens with NaNoWriMo too. But in the long run, it

doesn't really matter.

Why

doesn't it matter? I mean, I set a goal and I didn't meet that goal. So

I should berate myself and feel bad, right? Yeah, I'm thinking no.

Because what did I accomplish? I wrote some poems. I probably wouldn't

have written them at all if I hadn't started the challenge. So I have

some bits of work that wouldn't have otherwise existed. That's not a bad

thing at all.

Also,

who's to say I won't finish the challenge eventually? I did last year,

though I didn't write the last poem until some time in May or June if I

remember correctly. I like the challenges and I'll probably go ahead and

tackle the rest on my own timeframe. So, in my mind, rather than

failing the challenge, I've produced some new work, challenged myself,

and now I have some new pieces I can market later, with more likely to

come.

In

fact, the thing I'm most worried about regarding this challenge isn't

that I didn't write all the poems in the time allotted, but that I can't

seem to find the notebook I wrote them in. Now that's a catastrophe...

Showing posts with label Random Musings. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Random Musings. Show all posts

Friday, May 10, 2013

Monday, June 25, 2012

Why I'm Learning Russian and Why You Should Learn Urdu or Maybe Tagalog

|

I’ll be one of the first to admit that I can go overboard when it comes to research. I like to follow trails wherever they lead and can spend months just reading when I should probably be writing the story.

One thing I’ve done under the umbrella of book research is learn languages. Languages have always fascinated me. When I was a kid, I remember spending hours poring over my mom’s college Spanish texts and even dipping into her text of Beowulf in the original old English (I guess it runs in the family). So when I decided to write about a Russian spy, it seemed natural to come home with a stack of Russian language books from the library, including the entire CD set of Pimsleur’s Russian courses, one of the best ways to get pronunciation and syntax drilled into your brain.

So why would I need to learn a whole new language just because my hero is from another country? I gave this a lot of thought because, let’s face it, learning a language is time-consuming, and there are all kinds of ways to handwave that kind of thing in fiction.

But I decided to pursue the venture, as much as it seemed like overkill. And I discovered that, yes, learning the language made me feel more comfortable with the characters.

My heroine is American but knows Russian, so knowing how the language feels in the mouth helps me add verisimilitude when she exercises her bilingual skills. That might sound weird but give it a try. My college Spanish teachers said to smile when you speak Spanish—it helps keep the words at the front of the mouth. Irish Gaelic seems to depend a lot more on the tongue. And Russian seems to be either way in the back of the throat or about to fall right out on your chin, depending on the word.

Another issue is syntax and word choice. Without knowing something about the language, I wouldn’t have known why Russians tend to drop articles (there are no articles in Russian). I also wouldn’t know what English words are difficult for Russians to pronounce. (As far as what Russian words are difficult for English speakers to pronounce, the answer is all of them.)

Of course I could figure out a lot of this listening to Russians speaking English on YouTube. (Which, by the way, is a great reason to watch hours and hours of Evgeni Malkin and Alexander Ovechkin interviews and call it work.) But knowing the reasons why they speak like they do makes it easier to remember what my personal Evgeni will sound like when he speaks English.

There are also scenes when both characters are speaking Russian. In these cases, it’s easy to fall into a pattern where they talk as if they were both speaking English, idioms and all. But it’s more realistic to reflect some of the natural syntax and idiomatic usages of Russian. I want there to be a distinct “feel” to the dialogue based on what language is being spoken and who’s speaking it. I think it’ll add something to the story.

So I’ll keep plugging away with my Russian lessons. Maybe down the road I’ll know it well enough to follow the KHL. In the meantime, here’s a challenge—if one or more of your characters speak something other than English, see if a bit of study of their native language gives you different insights into how you write them.

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

The Rhythm Of The Words

For me, there is a certain rhythm to writing a book. It’s

not something I can just sit down and do, word after word, sentence after

sentence, progressing through a logical sequence until the story has spun

itself out on my page. There are, instead, phases to the process. Some of these

phases look like active artistry. Others look like pre-work or preparation.

Still others look like failure.

It’s taken me a long time to learn to trust this process, and in many ways I still don’t. I look at it askance, wondering if the pieces that feel like failure really are, if this is the time that the sequence will fall apart, like a zipper that has suddenly lost a vital tooth.

Because it feels that way sometimes—no, every time—when that spot comes in the writing when all the pieces are there, but they’re scattered, some here, some there, some ends tied off neatly, others frayed and broken. They couldn’t possibly all come together to form that final, tight weave that fashions story.

But they do. Eventually, they do.

I can’t make them do this. Sometimes sitting down to write, putting pen to paper, is enough to coax the flow and bring the various bits into alignment. But other times putting pen to paper is an exercise in futility. Nothing comes, or if it does come, it’s forced and twisted, broken, or it’s like trying to weave a stick into fine linen. It just doesn’t fit.

It’s then that I have to wait. It takes such patience, such trust, to just wait. I want to dive into the story again, to find all those loose bits and make them no longer loose, but on the days that require waiting, they simply won’t fold into each other. They’re ragged and sharp and stubborn. They don’t want to be.

Waiting, though. Waiting with the words, with the pieces. Hiding from them. Letting them hide from you. Lifting them into the light and examining them, like jewels under a loupe, looking for the flaws and the perfections. Ignoring them, then examining them far too closely.

It’s this constant handling, dropping, picking up and examining that finally lets me find the pieces where a story line has gone astray, or the place where I planted a clue I didn’t even know I’d written. When I find the flaws and the ways to smooth them out, or the underlying themes I didn’t know were there. Only then, after this careful and constant, trusting search, can I finally pull all those pieces together into a unified whole.

Only with the constant, steady practice can you learn to trust those silences. Only when you’ve let the process happen time after time, watching it, exploring it, can you truly believe that the story will find its way, with you or without you.

Constancy. Practice. Diligence. Trust. When these all come together, the result is the miracle that is a completed work of written art.

It’s taken me a long time to learn to trust this process, and in many ways I still don’t. I look at it askance, wondering if the pieces that feel like failure really are, if this is the time that the sequence will fall apart, like a zipper that has suddenly lost a vital tooth.

Because it feels that way sometimes—no, every time—when that spot comes in the writing when all the pieces are there, but they’re scattered, some here, some there, some ends tied off neatly, others frayed and broken. They couldn’t possibly all come together to form that final, tight weave that fashions story.

But they do. Eventually, they do.

I can’t make them do this. Sometimes sitting down to write, putting pen to paper, is enough to coax the flow and bring the various bits into alignment. But other times putting pen to paper is an exercise in futility. Nothing comes, or if it does come, it’s forced and twisted, broken, or it’s like trying to weave a stick into fine linen. It just doesn’t fit.

It’s then that I have to wait. It takes such patience, such trust, to just wait. I want to dive into the story again, to find all those loose bits and make them no longer loose, but on the days that require waiting, they simply won’t fold into each other. They’re ragged and sharp and stubborn. They don’t want to be.

Waiting, though. Waiting with the words, with the pieces. Hiding from them. Letting them hide from you. Lifting them into the light and examining them, like jewels under a loupe, looking for the flaws and the perfections. Ignoring them, then examining them far too closely.

It’s this constant handling, dropping, picking up and examining that finally lets me find the pieces where a story line has gone astray, or the place where I planted a clue I didn’t even know I’d written. When I find the flaws and the ways to smooth them out, or the underlying themes I didn’t know were there. Only then, after this careful and constant, trusting search, can I finally pull all those pieces together into a unified whole.

Only with the constant, steady practice can you learn to trust those silences. Only when you’ve let the process happen time after time, watching it, exploring it, can you truly believe that the story will find its way, with you or without you.

Constancy. Practice. Diligence. Trust. When these all come together, the result is the miracle that is a completed work of written art.

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Why Being Edited Is Like Getting Your Eyebrows Waxed

| |

| I only wish my eyebrows looked this good. sxc.hu/heidijean |

I have bushy, annoying eyebrows. They have a good general

shape, but they develop extra growth all around the edges and sometimes decide

they want to try to make a unibrow. It’s pretty annoying. I hate to pluck

because it hurts, and I’m a huge wimp. I’ve tried threading, and got great

results, but wow—I nearly passed out. My tattoo hurt less than that.

So my eyebrow grooming approach of choice is waxing. They

let you lie down on a massage table, or sit in a comfy chair, and they put

nice, warm wax on your eyebrows. Then they rip it off in one fell swoop. Yeah,

it hurts, but it’s over quickly, unlike plucking and threading, where they just

keep ripping stuff out in one horrifying stab of pain after another.

Oh, but then the waxers aren’t done. Because after they wax,

then they pluck. They have to clean up

all along the edges, get the shape just right, and get your eyebrows looking

like they both belong on the same face. It’s a tricky business. And sometimes

they take out too much, and you have to go to the grocery store and buy eyebrow

pencils. Or they don’t take out enough, and you wonder why the heck you gave

them your hard-earned $15, plus tip, just to wave the wax in the vicinity of

your still-hirsute brow.

How is this like editing? If you haven’t figured it out by

now, I’m guessing you’ve never been diligently edited.

You start with rewrites. Not always, but often. You get a

manuscript back that you thought was in pretty good shape, but it’s all annotated

with bits about how you have holes in your plot, or your characterizations

aren’t consistent. Scattered throughout are probably bits of detritus like

spelling errors, grammar mistakes, typos, formatting issues, etc. So you grit

your teeth and do the work, figuring hey, as much markup as there is here,

there can’t be much more left to do after this, right?

Wrong.

The story comes back again. Move this word here or over

there. Is this the right word? This sentence doesn’t quite make sense. I think

a comma here would make things clearer. And maybe this happens two or three

more times, until your eyes are watering from the pain and all you really want

is for somebody to spread that nice lavender oil over your eyebrows so the pain

will go away and everything won’t look all red and swollen.

But the tweaking is an important part of the process. It’s

the fine-tuning that gives you just the right quirks so you can have entire

conversations with the lift of a brow. You’re striving for—well, not

necessarily perfection, but something clean and sleek that fits your style.

It’s worth the pain in the end.

Beware, however, of the editor who plucks too long (and the

author shouldn’t do this either). Too much tweaking, and you’re scrambling for

the eyebrow pencil to get some semblance of your personality back. But perhaps

worse than that is the editor who doesn’t do enough, and leaves your manuscript

only partially shaped, its unibrow glaringly obvious for all to see.

Labels:

Editing,

Random Musings,

Writing Tips

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

Why Editing is Like Sculpting a Masterpiece

|

| Editing: Finding beauty in chaos. sxc.hu/andyvu |

When I edit, which I do almost as much as I write--some days more--I try to address the story on several levels.

- The story level. Does everything make sense? Is the structure compelling, leading the reader from one scene to the next without confusion? Does it meet the requirements for the genre? Are the characters consistent?

- Story detail level. Here's where I look at things like description consistency--eye color, clothes, hair color, spelling of names--things authors sometimes change by accident as they're writing.

- Grammar and clarity. This can be tricky, as this part of the process drills down to the author's choices word-by-word. Sometimes markup here is easy--if a sentence is grammatically incorrect, or the author uses the wrong word, changes need to be made. If a sentence throws me off as a reader, so that I don't understand what the author is trying to say, then that too should be addressed. However, if a sentence structure, word choice, or grammatical construction is integral to the author's voice, then changes should be carefully considered. Sometimes there's a find line between a stylistic choice and an easily understandable sentence, though, and it's important to keep the author on the right side of that line, for the sake of the reader.

In many ways, this process is like carving a sculpture. Anything that gets in the way of the story itself is removed or modified. Large issues come first, then lower level issues are carefully chipped and carved away.

Unfortunately, this can't always be accomplished in one editing pass. Sometimes it takes one pass for the larger issues and other passes for the fine-tuning. Then the editing really becomes like sculpting--taking away the larger bits first, then working down to the details. When this takes severla passes, it can be frustrating for the author, but the best editors always ahve the best interests of hte story at heart, even when it feels like they're being overly picky or obsessing over every detail. In the end, if you and your editor work well together, your story will be the better for the hard work.

Next time: Why Being Edited is Like Getting Your Eyebrows Waxed.

Labels:

Editing,

Random Musings

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Thoughts on writing—where do ideas come from?

|

| photo from sxc.hu by christgr |

One of the first questions people tend to ask when you

revealed the terrible secret that you’re a writer is, Where do you get your

ideas. (After, What do you write, at which point you have to decide whether to

say you’re working on the great American novel or books about vampires.) it’s

an interesting question, and one I’m never sure how to answer.

I get ideas everywhere. I carry little notebooks in my purse

so I can jot ideas down when they drop by. I have notebooks, folders, filing

cabinets, binders full of ideas. I wake up in the middle of the night with

ideas. My best friend feeds me ideas, usually as part of a nefarious plan to

get me hooked on hockey.

I think most writers suffer not from a lack of ideas, but

from idea overload. When I’m starting a new project, sometimes I look at the pile

of ideas and have no idea where to start. Which one is the most marketable?

Which one can I sell right away? Which one is most likely to land me an agent?

It’s enough to paralyze the creative mind.

Capturing ideas can be tricky, too. Thus the notebooks. But

how do you jot down an idea that comes as an image, or a feeling? Sometimes you

can’t. Then you have to let the idea move where it will, in and out of

consciousness, until it appears in a form you can easily add to your idea pool.

Or what about that idea that just gets away from you? The

one that came to you at 2 a.m and you couldn’t wake up enough to write it down?

If you’d written it down, it definitely would have been a bestseller, right?

Maybe, maybe not. My theory is that if it really was a good

idea, and one I was meant to have, then it’ll come back. It’s like that old

saying: If you love something, set it free. Some people aren’t comfortable with that

idea. It used to bug me, too. Now I’m on medication.

Ideas come from everywhere, but the best ones can be

elusive, or hard-won. These are the ideas that come back again and again,

demanding to be written, each time with a few more layers, a bit more guidance

about how the story should take shape. These are the ideas that are worth gold.

When you find those, you’ll know. Capture them and let them grow.

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

Familiarity Breeds Contentment

A splash of gold

On pine-swathed breast;

The mountains lay

The fall to rest.

If you live in the mountains in Colorado, there are certain things you can be sure of. During the summer, to avoid traffic, go down the mountain on Friday and up the mountain on Sunday to avoid campers going the opposite direction. This applies doubly to Labor Day and Memorial Day weekends, except shift the Sunday to Monday.

Oh, and it’ll happen again on one weekend in mid to late September or early October.

That last was tricky. It’s never the same weekend, so you have to pay attention to the news or other media outlets to find out when it’s going to happen.

It happened this past Saturday. I was driving the kids downtown to celebrate my first anniversary of self-employment and my son’s eighteenth birthday, which will happen on Wednesday. Traffic was backed up in front of the road where I turn onto the highway. In fact, it was backed up nearly ten miles, in some stretches slowed to stop-and-go.

“What the heck?” I said to the kids. I saw no sign of an accident, and Saturday afternoon isn’t prime camping traffic.

Then it struck me.

The traffic was backed up for ten miles because everybody was heading into the mountains to look at the trees.

Growing up in the Midwest, I always had lots of trees to look at in the fall. Oak, maple, poplar—they smeared every fall landscape with reds, oranges and yellows.

In Colorado, it’s the aspens. Just the aspens, in masses and patches of brilliant gold set against the deep green of pines. It’s really quite stunning to see them high color. Aspens share root systems, so they grow in groves, all of which change color at roughly the same time.

This weekend was the prime weekend. That’s the thing about the aspens. If you went this past weekend, you will have seen the glorious display of hundreds of golden leaves shimmering in the breeze. Next weekend? It’ll all be brown, dead and gone. It’s a fragile thing. The beauty of the color depends on vagaries of weather, including temperature and rainfall, that I’ve never been able to figure out. People in the news media here do calculus while standing on their heads to determine the exact day that the color will be at its peak.

The color is vibrant this year, a darker, richer gold than I’ve seen in a long time, probably because we had a crazy-wet summer. But we didn’t go up the hills to Kenosha Pass or Guanella Pass or Mt. Evans. Not this year.

Instead we went around about our regular business. At the library, I looked up to see two huge patches of aspens in the peaks beyond, stunningly brilliant against the surrounding deep green. More golden splendor lurked between peaks I see every day, now transformed so that I couldn’t help but look and marvel a little as we drove down to lunch. At Meyer Ranch Open Space Park, I saw patches of red among the gold. And following the bends in the highway, I saw streaks of aspen groves like molten gold poured down the sides of the mountains.

It’s nice to go somewhere special to see the aspens. At Kenosha Pass, there are huge groves, so everywhere you look, there’s nothing but gold. At Mt. Evans, the swathes of gold highlight the towering, rugged flanks of 14,000-foot peaks.

But seeing that same gold scattered over my familiar landscape struck me more deeply this year than past treks to Kenosha have. This year the aspens were a special gift, one I didn’t have to seek out, but that instead was scattered all around me, in familiar places that were made special, gilded by the dying leaves.

I think I liked it better this year.

Labels:

Colorado,

Miscellaneous,

Random Musings

Monday, September 26, 2011

Persistence of Memory

My earliest memories are buried deep. They bubble up from time to time, but not as often as they used to. Some of them are strange. I’m not sure all of them are real.

My earliest memories are buried deep. They bubble up from time to time, but not as often as they used to. Some of them are strange. I’m not sure all of them are real. I remember being in a cave. It is dark and close, and I feel like I’m alone. There are vague lights here and there. The darkness isn’t threatening. It just is

I remember lying on a mattress watching TV. On the screen is a rocketship in a scaffolding, ready to launch. There is a black cat. The room I’m in is small, and I have to look up to see the TV, which is sitting on a dresser.

I’m not sure where the memory of the cave comes from. I know my family visited Carlsbad caverns when I was very young, but whether this cave is related, I’ve never managed to find out. Maybe it was a dream. Maybe I’m remembering the womb. Maybe it’s nothing significant at all.

The TV sequence was a real event. The show was Star Trek, and the episode I was watching was from the third season, not long before the original series was canceled.

Is there a point to this? I don’t know. Maybe that reality is so subjective we can’t even be sure our memories feed it back to us accurately. Do we really remember what we think we remember? If we’re made of our memories, does this inaccuracy have a fundamental effect on our psyche?

In the end, does it really matter?

Labels:

Miscellaneous,

Random Musings

Monday, September 12, 2011

What I’m Reading—Earth’s Children—Plains of Passage

|

| Photo from bn.com. Affiliate link. |

Some believe that, long ago in our prehistory, this was not the case. Before human beings could record their beliefs in written language, there might have been a belief system based on a Mother Goddess. These speculations—and unfortunately they are just speculations—are based on art from this prehistoric period. Before we had written language, we had art, and much of this art is interpreted to support the idea of a matriarchal society and a companion Goddess-based religion.

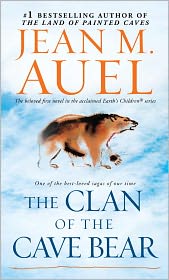

Lately I’ve been re-reading the Earth’s Children series by Jean Auel. I first read the first three volumes many years ago, and now that there is another book to be had, I decided to pick them up again.

In these books, Auel recognizes the school of thought that believes our earliest belief systems focused on a goddess. But her presentation, to me, doesn’t stay true to this vision.

In Clan of the Cave Bear, we meet the Clan, a group of Neanderthals who take in Ayla, the too-good-to-be-true heroine of the series who is presented as a modern human. The Clan worships an Earth Mother, but their society is structured in such a way that males and females hold tightly proscribed roles. Men hunt and do manly things. Women are mothers, healers, and preparers of food. And ne’er the twain shall meet, as Ayla discovered when her more flexible brain realizes she is perfectly capable of hunting.

More disturbingly, the females are expected to make themselves sexually available at a signal from any male in the tribe. Auel attributes all these characteristics of the Clan culture to a racial memory. All the Clan hold these memories, which go all the way back to the primeval goo. A neat idea, but also far too easy an explanation for a culture that supposedly believes in a Mother Goddess, yet subjugates all its women.

The belief systems of the more modern humans, represented by Ayla’s eventual lover Jondalar, seems very different at first. Women are free to perform any duties they find appropriate to their skills, from hunting to cooking to sacred prostitution. The role of certain women in initiating men sexually aligns with many of the ideas of how a Goddess-based society might have worked. Women are also initiated by chosen men, “opened” so that male spirits can enter their wombs and impregnate them. (The idea that, at this point in history no one but Ayla was able to figure out the relationship between sex and pregnancy is another major quibble.)

Ayla finds herself in a position to express herself more freely as a woman and an individual as she travels with Jondalar, and learns more about his people and their relationship to Doni, their mother goddess.

However.

A sub plot in Plains of Passage, to me, undermines this idea of an idyllic Goddess-based belief system. A young woman in a tribe Ayla and Jondalar visit has been gang-raped by a group of thugs who have been similarly harassing the Clan females in the area. (Another aside—the Clan response to the rape of their women is generally, “But they didn’t give us the signal. If they’d just given the proper signal, we would have been happy to succumb to their demands. It’s what a good Clan woman does.” Also cringe-worthy.)

This young woman, who has suffered this horrible violation, is not treated with love and respect. Instead, her family is devastated that their virgin daughter was taken sexually before she could be properly “opened” by an approved male in the relevant ceremony. And in order to be acceptable to the eligible males in the tribe, she must be cleansed in a special ceremony—performed by a man.

This strikes me as severely ridiculous. The idea of a woman being “ruined” by rape—or, for that matter, by consensual sex—is part and parcel of a patriarchal mindset. Why in the world would a Mother Goddess place these kinds of proscriptions on women? Rules that allow a man’s actions to define a woman’s status?

To me, Auel’s portrayal of the belief systems of these people is deeply rooted in the misogynistic prejudices of current religion, particularly Western ideologies. In addition to this bit of nonsense, her tone toward the Clan is consistently positive, as if the limited roles allowed women in this culture, not to mention the virtual sexual slavery enforced upon them, is actually better than the more liberal ideas presented by Jondalar’s people. And Jondalar’s people, while making obeisance to a goddess figure, and holding the Mother above all others, still hold the idea that a woman’s worth is judged by the condition of her genitals.

This seems to be to be a far cry from the ideology proposed by many who have conjectured and theorized about the makeup of the Goddess culture. If this kind of belief system actually existed, I hope it was far more accepting of women—who are, after all, the embodiment of the theoretical Goddess—than Auel’s version.

In my own books, as I continue to work on research in the course of building stories set in the Five Lands, I’m also struggling with the way men and woman would relate to each other in societies that are extremely matriarchal, extremely patriarchal, or some combination of the two. I’m not sure I’m happy with what I’ve done so far with these ideas in Ring of Darkness. But as the stories grow and evolve, I hope to incorporate elements of a matriarchal society and how it could function in ways that don’t carry with them ingrained prejudices of our own largely patriarchal world.

Labels:

Random Musings,

Reading,

Ring Saga

Copyright 2009 Katriena Knights. Powered by

Blogger.

Blogger Templates created by Deluxe Templates

Designed by grrliz

Blogger Templates created by Deluxe Templates

Designed by grrliz